what do i do if i dont have access to clean water at home

Bend Lake Kickoff Nation, a forested community in southern Canada, is surrounded on three sides by fresh water.

Only for decades, residents have been unable to safely make use of information technology. Wary of crumbling infrastructure and waterborne illness, the community instead relies on shipments of bottled water. The community's newly elected chief, aged 34, has lived her whole life without the guarantee of make clean water flowing from the tap.

"The emotional and spiritual damage of non having make clean water, having to expect at all of the water surrounding us on a daily footing and unable to use information technology, is well-nigh unquantifiable," said Chief Emily Whetung.

Amid mounting frustration, Whetung and other Indigenous leaders have launched national class-action lawsuits confronting the federal government. Arguing the federal regime failed to provide clean water and forced communities to live in a manner "consistent with life in developing countries" they are suing the government for C$2.1bn (US1.7bn) damages – the costs associated with years of bottled water trucked and a water treatment organization for the whole community.

Despite beingness one of the nearly water-rich nations in the earth, for generations Canada has been unwilling to guarantee access to clean h2o for Indigenous peoples. The water in dozens of communities has been considered unsafe to potable for at least a year – and the regime admits it has failed.

In 2015, Justin Trudeau, then campaigning for the state's superlative task, made an ambitious hope to cease the scourge of unsafe water in more than 100 Offset Nations communities across the country. But today the federal minister overseeing the consequence acknowledges the government has missed its March deadline on its own five-year promise, and says he has "no credible alibi" for how communities that take gone decades without clean h2o still lack access.

"It'south unacceptable in a country that is financially ane of the most wealthy in the world, and water rich, and the reality is that many communities don't have access to clean water," the federal Indigenous services minister, Marc Miller, told the Guardian in an interview.

Access to drinking h2o is something few Canadians ever have to think twice about. But the vast geography of Canada and the disparate locations of 630 First Nations communities – some accessible but by plane – makes setting upwards water treatment infrastructure a logistical challenge.

Every bit a consequence of colonial-era laws, Indigenous communities accept been barred from funding and managing their own water treatment systems, and the federal government bears responsibility for fixing bug.

"If you lot are anywhere else in Canada and you turn on the tap, then you are protected by prophylactic drinking water regulations," said Amanda Klasing, a water researcher at Homo Rights Watch. "If you live on reserve, no such regulations exist. There are no safe drinking water protections."

Sure communities, like Curve Lake, take issues with E coli in their water. Others, like Grassy Narrows, struggle with a legacy of toxic heavy metals, a remnant of negligent industry. In some cases, h2o is tainted by parasites and bacteria that occur naturally. In others, reactions between organic material and chemicals used to purify water tin can create unsafe water.

In outcome, the government issues advisories warning against using the h2o, and some have been in identify for decades. The customs of Neskantaga in northern Ontario, has been nether a water advisory since 1995, researchers establish, despite having a water treatment plant. In Manitoba, Shoal Lake twoscore'south water advisory has been in place since 1997. Plans for a water treatment constitute were scrapped in 2011 after the federal government balked at the toll of the project.

In those communities, children take sores and skin diseases like eczema. Others struggle with gastrointestinal disorders.

For Whetung, Bend Lake's battle to go clean water encapsulates the struggles of many First Nations communities.

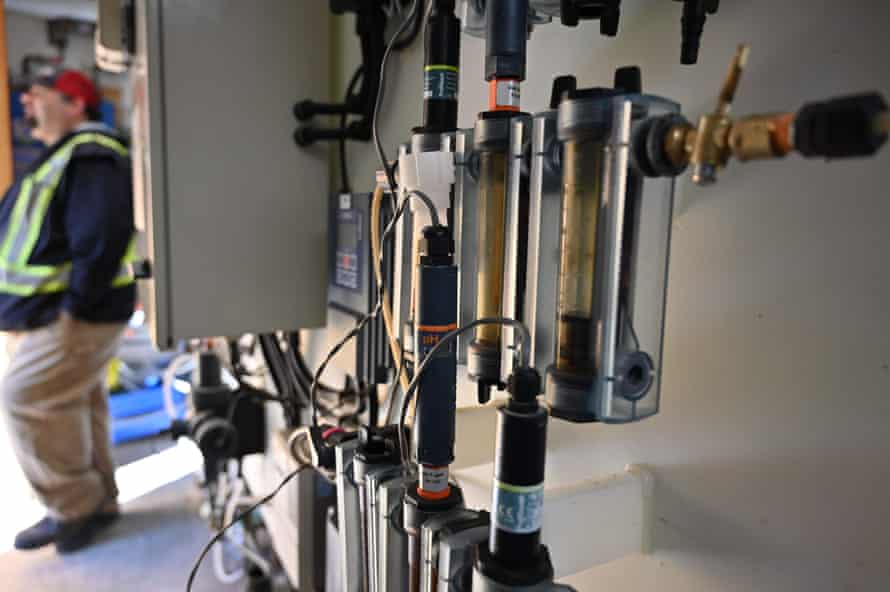

When Bend Lake'due south water treatment plant was congenital in 1983, information technology was intended to serve a population of merely 56 and had a shelf life of 20 years. Despite quickly outgrowing the chapters of the plant, decades of hierarchy have stalled the community'south ability to upgrade their infrastructure. As a result, the community has dealt with multiple drinking water advisories over the years, including a contempo boil-water advisory that lasted most two years.

An inspection of the found by Ontario'due south ministry of environment found a filter that wasn't removing pathogens and malfunctioning ultra-violet handling. While the ministry building determined the community was in urgent need of a new plant, at that place was nothing the province could do: the establish was the responsibility of the federal government, which deemed the take chances to be lower. The federal authorities has approved pattern plans for a new facility, only construction is withal years away.

Until that plant is built, the shipments of bottled h2o volition continue.

"Water is life," said Whetung. "Information technology's what nosotros grow our children in when they're in the womb. And nosotros tin't utilize any of what we have admission to."

Since he first took function, Trudeau'southward authorities has made meaning progress on the issue, investing more than than C$2bn. In 2016, there were 105 communities with long-term drinking h2o advisories in place –meaning the water had been unsafe to use or eat for at least a year. As of late April, that number is down to 52 advisories in 33 communities.

The federal government says the effigy remains high because of delays arising from the coronavirus pandemic, and information technology has pledged some other C$1.5bn in funding.

Merely a scathing report from Canada'southward auditor general at the end of February found that the federal government had failed to invest sufficient resources in the task and that much of the work was lagging even earlier the pandemic striking.

"I am very concerned and honestly disheartened that this longstanding issue is withal not resolved," the auditor general, Karen Hogan, told reporters, warning it would be years before some communities have their advisories lifted. "Admission to safe drinking water is a basic human necessity. I don't believe anyone would say that this is in whatsoever fashion an acceptable situation in Canada in 2021."

The auditor also institute that a number of the drinking water advisories that the authorities lifted were the result of interim measures rather than long-term upgrades.

And the crisis may run deeper. Experts caution that federal monitoring does non include wells, even though xx% of First Nations communities rely on them to supply water to most homes. Nor does the authorities rails waterborne illnesses in First Nations communities, or potential deaths that could be related to water quality.

"It seems unbelievable that in that location are communities that have dealt with drinking water advisories for more than two decades," said Charles Hume, an elderberry with the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. "We're non looked at the same … nosotros're actually the final on the totem pole."

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/30/canada-first-nations-justin-trudeau-drinking-water

0 Response to "what do i do if i dont have access to clean water at home"

Post a Comment